Photo by Dr. William Precht.

A recent study published in Science Express by Dr. Kent Carpenter of Old Dominion University and a consortium of nearly thirty coral reef ecologists has determined that one-third of coral face increased extinction threat due to climate change and local anthropogenic influences. Carpenter refers to the current problem as “the human meteor”; in reference to the meteor impacts that helped send the dinosaurs hurtling towards extinction at the end of the Cretaceous Era. At that time, one third of extant coral species went extinct along with dinosaurs.

Online colleague and co-blogger Jennifer Jacquet at Shifting Baselines has a nice summary of this and other dire tales coming out of the 11th International Coral Reef Symposium held in Ft Lauderdale, Florida last week. Ed Yong at Not Exactly Rocket Science also has an insightful summary of Carpenter’s analysis and its implications. Below, I go on at length about other implications of the Carpenter study, particularly in relation to some other talks held at the conference last week.

I stood in the room as Dr. Carpenter announced the results yesterday afternoon. He made some very interesting points in response to his commenters, so I will use the opportunity of this occasion (our 1000th post at ScienceBlogs!) to highlight some implications of the study that may not be evident in the article itself. For example, commenters asked whether Carpenter’s group is predicting global species extinction or localized expatriations, and whether the plight of the corals is more akin to the buffalo, whose numbers declined steeply, yet survived extinction thanks to human intervention, or whether the plight of corals is more akin to the dodo, which is truly extinct. We might also ask will corals migrate north, or retreat to deeper waters like the coelacanth?

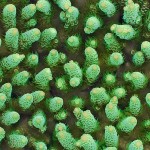

Reef building corals thrive in warm, oligotrophic waters, so northward migration may not be a simple solution due to a number of factors, including riverine inputs. According to the “naked coral hypothesis”, corals might even survive in a decalcified state, or diverge and adapt. Either way, on human time scales, we lose diversity. The problem is, our reefs are changing rapidly. The most dramatic reef builder in the Caribbean, elkhorn coral Acropora palmata, is already endangered; but in some places, like Jamaica, there is hope. Another reef builder, staghorn coral Acropora cervicornis is in the midst of recovery (see photo above).

At the conference, Dr. Carpenter stated he feels the plight of corals is most akin to the plight of the buffalo. Corals can be saved by human intervention. He pointed out that his team evaluated “extinction risk”, which is not the same as “population status”, and while this new union of concerned scientists cannot say these coral species are absolutely going extinct, they can say that coral reef habitat is in serious decline. Carpenter added that the metrics of the study were highly conservative, not to risk a poor interpretation. For instance, ocean acidification was not considered as an extinction threat, though many believe it to be true, because the problem is not yet clearly defined. But Carpenter also stated that 200 coral species were identified as “vulnerable”, and that if their status were to tip towards “endangered”, nearly 60% of coral species would face extinction. This is a sobering thought to any scuba diver. Grow up quick my children, or you might miss the sight of these reefs altogether.

The reasons why coral reef degradation is happening all around were evident in many of the 1000 coral presentations at ICRS from reef researchers from all over the world. If I were to list the Top 5 problems facing coral reefs in order of scientific consensus, I would dare say that fishing is the number one problem, because target species are broad, ranging from large predators like sharks and groupers to important herbivores like surgeonfish, tangs, damselfish, and wrasses. Even the corals themselves are fished for the aquarium trade. The idea of a healthy reef is changing even now. Line Islands is remote island chain naturally protected from fishermen, for example. Here, the sharks rule, and reef fish populations are depressed by predation. See National Geographic for a summary of Enric Sala‘s hypothesis of an “inverted pyramid” where greatest biomass is found at the top of the food chain.

The remainder of the Top 5 reef problems by consensus could be argued between nitrification and water quality degradation caused by nearshore run-off, increased severity and rates of disease and infection in invertebrates, perhaps brought on by global warming, and finally ocean acidification due to extreme concentrations of carbon dioxide in the global industrial atmosphere. I may have missed a few common insults to coral reefs here, but you can remind me in the comments.

So, is it all over for corals? Are they the canaries in the ocean’s coal mine? Should we wave bye-bye to corals forever? You may know what I am going to say. What about the deep-sea corals, like the stylasterids and cup corals? What about the gorgonians? These are corals too!

Cup corals must be safe in 3000-6000 m of water, but these are not reef builders. Lophelia pertusa ranges from 300-1000 m in the Gulf of Mexico. The species is definitely an ecosystem engineer, though, and forms extensive reefs. But she’s been hard hit by oil exploration and development in the GoMx, and by bottom trawlers in the North Atlantic. So, Lophelia is facing increased extinction risk. Gorgonian corals were excluded from this analysis. Yet, bamboo corals and precious corals are threatened by harvest for the jewelry trade. Primnoa spp. and bubblegum corals are regularly trawled over. So it seems almost all the foundation species are in trouble in one way or another, no matter how deep you go. Carpenter noted that the Global Marine Species Assessment will include new groups in the future, particularly the echinoderms. I’m crossing my fingers that gorgonians get their moment in the sunshine sometime soon.

Let me tell you that octocorals got a very BAD RAP at this here ICRS meeting. Apparently, Xenia spp. invaded some coral reefs in Malaysia and biologists are quite upset about it. Soft corals were trotted out more than once as a “degraded state”, an “alternative stable state” or an “intermittent reef state”. Frankly, the soft corals were slapped in the face like an old man in need of Viagra. So, let me be the first to say “gorgonians are not soft corals”. They have a rigid axis, OK? And they can be huge, like 1 m tall and more.

Consider this especially in the context of stoloniferous modes of reproduction and the invasive species problem. Zoanthids and corallimorphs are soft corals, but I challenge any coral taxonomist to tell me that antipatharians (black corals) are soft. So let’s get this straight people, gorgonians are octocorals, and antipatharians are zoantharians, but they are not soft corals. Not even the old ones.

At this writing, I move to reinstate the Order Gorgonacea, regardless of what the genes say. Its just not safe to hang with Alcyonacea anymore! If you’re with me say “Aye”. All aboard? OK, then. Wow. I love open access taxonomy.

At this point, you may be asking yourself, “is there any GOOD NEWS from the 11th ICRS”? The answer is “YES, there is GOOD NEWS”. For example, there is a growing consensus that some coral reef fish disperse long distances. Scott Hamilton from UC Santa Barbara demonstrated these fish are generally in better condition than local recruits, so upstream reefs can be expected to help “re-seed” down stream reefs in a marine protected area network. They may also disperse around islands, but most will not disperse across 50km of open water between islands, says Dr. Steve Palumbi. On the flip side, lionfish are reef fish, but these are dispersing long enough distances along the North Atlantic coast now to be called an invasive species. Octocorals feel for you, lionfish. You just can’t please everybody all of the time.

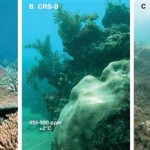

Perhaps the best news from ICRS was the discovery and documentation of large fields of Montastrea spp. growing in deep water (30-60 m) around Puerto Rico. This discovery was reported to the delight of many. It was even suggested by the session host Clive Wilkinson that these deep corals may aid in the recruitment and recovery of coral to degraded reefs. At least one instance of rapid recovery was reported over a ten year period following a disturbance on the island of Moorea, near Tahiti. Pulley Ridge is another deep reef system in the United States, located on the West Florida Shelf.

It is now safe to say that many deep reef systems are likely to occur in the Caribbean, and that these deep-reef sites may be healthier, somewhat sheltered reefs protected from surface water warming. However, this is not to say these deep-reefs are immune to fishing or disease. Nor are they likely they to exhibit the delicate diversity of warm, shallow coral reefs. The scientific consensus is that one third of shallow tropical coral species are clearly in trouble around the world. In my opinion, deep corals may be next to follow, unless we can get it together to do something now to stop bottom trawling and other destructive fishing practices.

Read more about Carpenter et al’s new manuscript here at Science Express, and treat yourself to an insightful interview with interesting perspectives by top notch coral reef ecologist Dr. Richard Aronson at the SeaWeb outreach and education website. Special thanks to Dr. William Precht for the terriffic photo above of a Jamaican coral reef in recovery, from the Seaweb website.

Their, not there. ;)

Carpenter noted that the Global Marine Species Assessment will include new groups in the future, particularly the echinoderms. I’m crossing my fingers that gorgonians get there moment in the sunshine sometime soon.

I always wonder if its possible my children will never know of a reef except as an expanse of skeleton or in an aquarium. Some of these problems have gone on too long, like trawling and fishing for aquarium use. I used to have a reef aquarium and some of those fish are so underpriced and undervalued. It’s a shame.

Thanks, y. Fixed that error. I hear what you’re saying about economic valuation. That’s a compelling point.

These five targets are right on the money! The approach to limiting fishing is working in the Philippines and Australia with benefits to fisheries as well as to coral reef health. Darwin Medal winner Terry Hughes highlighted these efforts at the International Coral Reef Symposium and emphasized the possible positive effects of focused efforts by our governments and each one of us. It’s not all gloom and doom, but immediate action is needed.

y, c’mon man. We don’t need grammar-nuns, especially those that can’t practice (or type) what they preach.

ahem “I’m crossing my fingers that gorgonians get there moment in the sunshine sometime soon.” (just being a smartass btw)

But what your saying is one my greatest fears, especially as my wife and I are raising 2 kids of our own. It is on my mind alot.

Kevin, I had mispelled “there” in that line and y was pointing it out. He/she forgot to put quotes to indicate that (major no-no), but generally I don’t mind folks policing our grammar.

Ron Karlson, thanks for reading! I wish I hadn’t missed that talk by Terry Hughes. He’s legend. Just too much happening there to keep up with, especially without a PROGRAM.

Apparently they ran out after the second day. I didn’t arrive until the fourth, unfortunately.

Peter, just being a smart ass because y made the same mistake he/she has riding you on lol.

Can anyone tell me the actual rise in water temperature at any of these reefs?

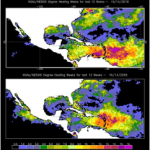

Jim, the metric for reef bleaching is not temperature, per se, but “degree heating weeks”, which I believe is the number of weeks above 1 or 2 standard deviations from normal. In the Western Pacific Warm Pool, average temperature is about 29 degrees C, if I recall correctly. There is talk of an “ocean thermostat” with a max temp of ~32 C (read J Kleypas), but I’m not sure if that’s a global thermostat or a regional one.

There is talk of an “ocean thermostat” with a max temp of ~32 C (read J Kleypas), but I’m not sure if that’s a global thermostat or a regional one.