I’m delighted to present this guest post from Dr. Michelle Staudinger, a post-doc at the University of Missouri Columbia and stationed at the National Climate Change and Wildlife Science Center in Reston Virginia. Michelle was a grad student at Stony Brook University while I was an Assistant Prof there another life ago. Thanks Michelle for this super insight into deepwater diversity! The Pisces team is still at it, so you can ask any questions for Michelle in the comments.

I’m delighted to present this guest post from Dr. Michelle Staudinger, a post-doc at the University of Missouri Columbia and stationed at the National Climate Change and Wildlife Science Center in Reston Virginia. Michelle was a grad student at Stony Brook University while I was an Assistant Prof there another life ago. Thanks Michelle for this super insight into deepwater diversity! The Pisces team is still at it, so you can ask any questions for Michelle in the comments.

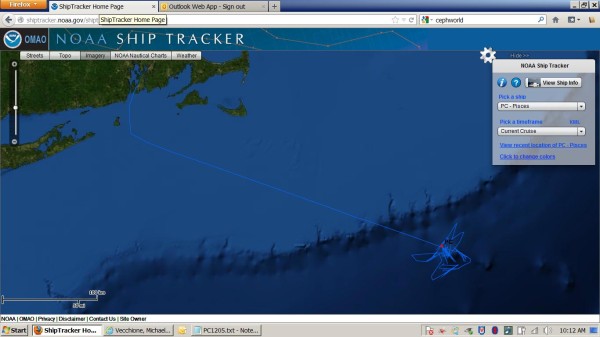

On Wednesday August 29th, the NOAA Ship Pisces left Newport, Rhode Island and headed east-southeast towards the Bear Seamount (39°55’N 67°30’W) for a 10 day research cruise. The Bear Seamount is an extinct undersea volcano located south of Georges Bank, inside the US economic zone, and is one of the 30+ seamounts that comprise the New England Seamount chain. Most of what we know about the fauna around Bear Seamount has been gained since the year 2000 from a series of eight research surveys; prior to 2000 however, this seamount was considered one of the most understudied in the world.

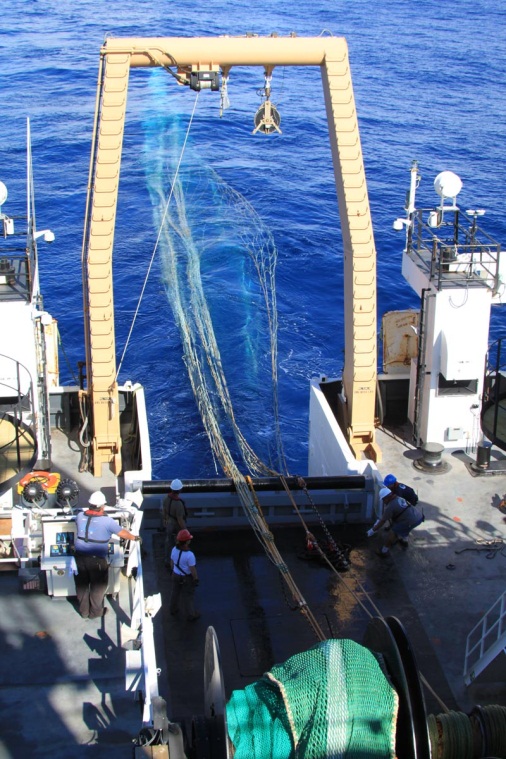

As was true of past research expeditions, the primary goal of this survey is to document and collect fishes, cephalopods, and crustaceans living in mesopelagic and bathypelagic habitats using mid-water and bottom trawls deployed at 600 – 1500 meters, and 1,000 meters or greater, respectively. What’s sets this survey apart from the rest of the series is that previous surveys were exploratory and this will be the first to collect quantitative data on community composition, and net catchability. Specimens will be archived in the collections at the National Museum of Natural History, Peabody Museum, the Museum of Comparative Zoology, and the Fish Collection at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science. There are also several graduate students and post-doctoral researchers onboard that have sacrificed their Labor Day weekends to collect data and samples for various research projects.

This cruise is a chance for many of us to see species we have only seen as drawings, or in photographs, and many species we have never heard of. In addition to the expected species based on previous surveys, we have already found at least one fish that may be a new species and a squid that, although common in the eastern North Atlantic and found on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, is not known from the western North Atlantic.

I have been in awe of the beauty and the alien-like appearance of many of the fishes and squids we have caught on this trip, and in this post I will be sharing pictures of just a few of the approximately 400 species we have seen so far. The pictures below barely capture the breadth of colors and unique forms that the Bear Seamount fauna supports.

- A small Lampadioteuthis megaleia. These squid are destined to be the newest craze for aspiring tween marine biologists. They come bejeweled in an array of colors – purple, opal, and of course pink.

About half way through the trip, we switched the mid-water trawl out for the bottom trawl gear and had some well-deserved time for relaxation and sleep. The students and post-docs soaked up some rays of sunshine on the front deck – since most of the sorting and measuring of species is done inside the wet and dry labs, this was the first vitamin D most of us got since we started trawling. Meanwhile, the chief scientist (Mike Vecchione) and taxonomy leads (Jon Moore and Tracey Sutton) caught up on some zzzzz’s. Jon confessed at one point that he had been awake for 21 hours straight and he said this with a wide grin (did I mention how excited people are to be out here?). I don’t think it would have taken much for him to stay up even longer if some new fish came up.

After days of sorting through sawpalate eels (Serrivolmer beanii) and Mastigoteuthid squids, the science crew was eager to see some new species. Then came the large roundnose and roughhead grenadiers, slickheads, and cutthroat eels! The floor of the wet lab was slick with slime, and in no time we were longing for our mid-water critters again. Bottom trawling at these depths is always tenuous because of the possibility of getting hung up on the volcanic rocks that protrude out of the seamount surface. We successfully completed two out of the three planned bottom tows before the net became un-repairable (for this mission anyway) as we need some replacement parts. Nonetheless, we got excellent samples from the first two attempts. Below are some highlights.

After days of sorting through sawpalate eels (Serrivolmer beanii) and Mastigoteuthid squids, the science crew was eager to see some new species. Then came the large roundnose and roughhead grenadiers, slickheads, and cutthroat eels! The floor of the wet lab was slick with slime, and in no time we were longing for our mid-water critters again. Bottom trawling at these depths is always tenuous because of the possibility of getting hung up on the volcanic rocks that protrude out of the seamount surface. We successfully completed two out of the three planned bottom tows before the net became un-repairable (for this mission anyway) as we need some replacement parts. Nonetheless, we got excellent samples from the first two attempts. Below are some highlights.

Our first tow after switching back to the mid-water trawling gear landed one of the biggest squids weve seen yet! A large Histioteuthis bonnellii, often refered to as a “jeweled squid” because of all of the photophores that cover its body. These squids are a favorite snack of toothed whales like the great sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus).

AD – You can follow more of what the Pices cruise is up to here: http://shiptracker.noaa.gov/shiptracker.html

EDIT – a commenter asked for crustacean images, so Michelle kindly provided some, these came from bottom trawls:

Share the post "Guest post: The stunning deep-water biodiversity of the Bear Seamount"

What an amazing array of life! I love that it’s all out there. And always has been. And I’m alive at the time when we can finally start seeing it for the first time!

You mention being interested in feeding habits. I’m curious, have you ever discovered plastics inside any of the creatures you examine? They found the first plastics in Gulf of Maine groundfish back in 1972, yet I believe since then there’s been no study done specifically to look at the issue.

Hi Harry, In my stomach content analyses of large pelagic fishes, such as dolphinfish, wahoo, tunas, sharks, and marlin we often find small bits of plastic, fishing line, and other garbage. However, these fishes are primarily feeding in the epipelagic zone where much of the “great garbage patch” plastic is. I haven’t opened enough stomachs on the Bear Seamount survey to say whether or not the fish we caught also have plastic in their stomachs, but I can tell you that when we did a bottom trawl, plastic came up in the tows – things like plastic bags and wrapping ribbon (like for birthday presents). So it is in the environment at 1,100 meters.

As a crustacean taxonomist interested in mesopelagic and bathypelagic shrimps, I’d be interested in photos of any of these.

Ive got a few pictures of crustaceans, hopefully we can add them to the blog soon.

Added. Technically the sea spider isn’t a crustacean, but they are arthropods, and so damn cool you just have to add them in when you got ’em :)

have to ask, can you eat blind lobster?

It would be be a lot of work for little reward, I don’t think there is much meat on the blind lobsters. Also, most of the deep sea fishes and cephalopods that people have tried to cook and eat have not had a palatable consistency, I’m guessing the crustaceans would be similar.

Good to see you’re still doing cool stuff Michelle. Has the feeding habits analysis been a regular part of the sampling or is it just something you’ve been sneaking in between tows? Also, I have to ask if there were any cool sharks (that catshark is pretty gnarly).

Unfortunately, I was not able to collect stomachs from too many fish on this trip as I had my hands full collecting lots of cephalopods. But we did catch some juvenile tunas, which I will do stomach contents and stable isotope analyses on when I return to the lab as part of a related project on large pelagic trophic ecology. The catsharks were the only sharks that came up in this trip, I wish there had been more.