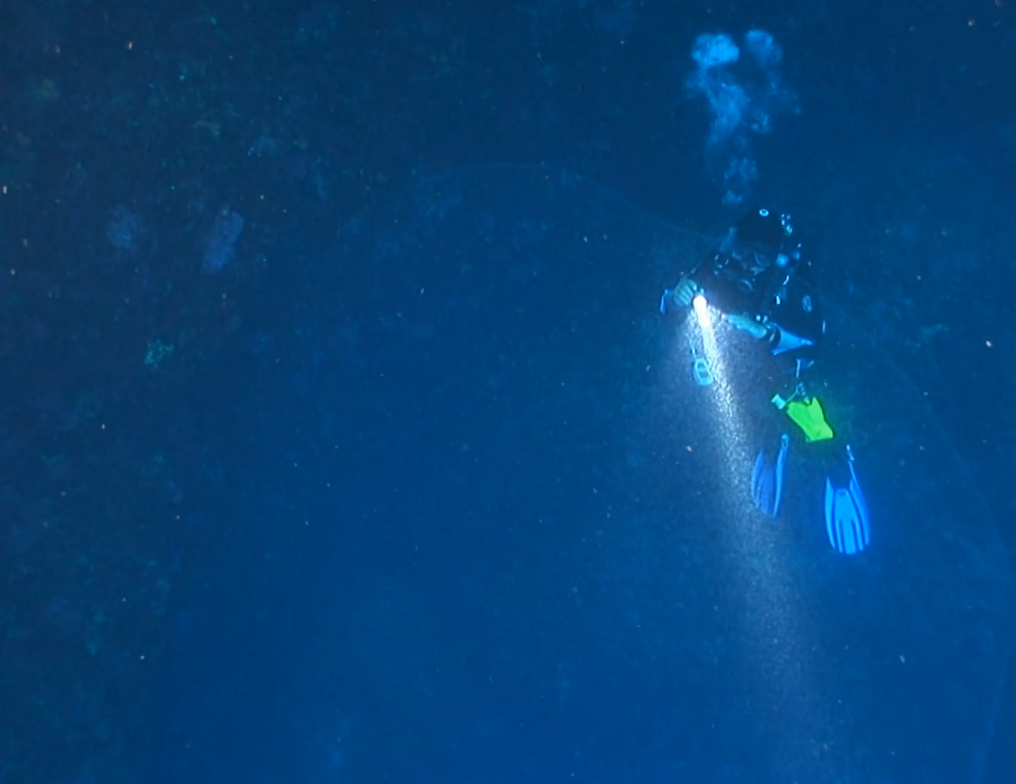

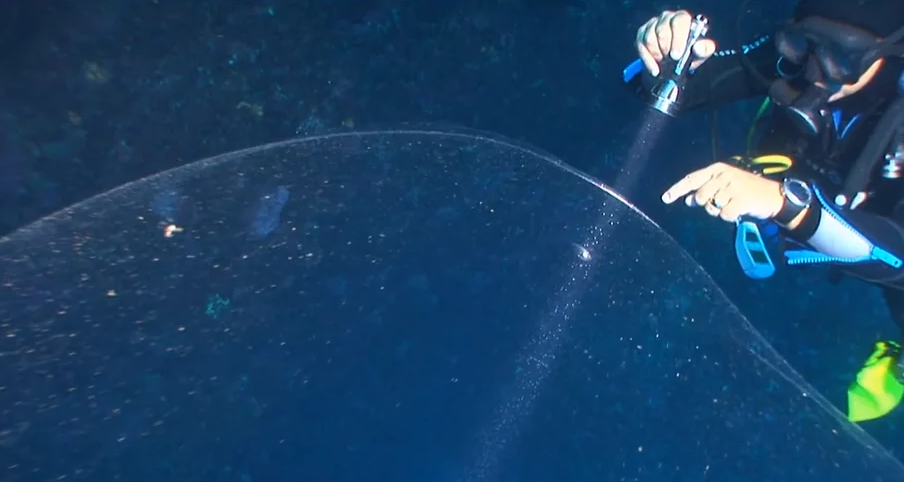

Oh July 9th, 2015 a group of lucky divers happened upon something truly remarkable–A 4-meter-wide clear sphere floating off the coast of a small town in Turkey. The sphere was 22 meters below the sea surface, and even up close, it appears almost invisible. But what exactly is it?

The divers didn’t know. Lutfu Tanriover, the videographer, told me via Facebook the group felt a mixture of both excitement and fear as they approached the mysterious blob. The blow felt “very soft,” and looked gelatinous. But only after the video went online did the mysterious blob get a possible ID. Dr. Michael Vecchione of the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History was the first to propose a suggestion. Dr. Vecchione is an expert on squid, and to him this giant sphere looks like a huge squid egg mass, and it’s the largest he’s ever seen. In fact, egg masses like this may be floating off many major coasts, not just Turkey’s. But what kind of squid, specifically, could produce a mass this big?

Dr. Vecchione best guess? A large red flying squid named Ommastrephes bartramii. These animal can grow to around 1.5 meters (~5 feet) in length. As their name suggests, red flying squid can fly, or rather glide, by jetting out of the water and flattening their tentacles and fins to make “wings”. They’ve also got arms packed with suckers complete with “teeth”.

But no one has actually seen a red flying squid lay eggs. Is the red flying squid even capable of producing an egg mass so big?

In all likelihood, yes. Only once has another egg mass this big been reported, and it belonged to one of the largest, most intelligent, and dangerous squid known. The humboldt squid is an oceanic velociraptor. Smart, strong, and agile, these 2-meter-long squid form packs, flashing quickfire communication to each other using specialized color-changing skin. In Spanish, humboldt squid are known as diablo rojo, or red devils. With a powerful parrot-like beak, and sharp teeth on their suckers, these squid have been documented to attack people. Their bite can break bones, and their strength can dislocate limbs. But they have a softer, gentler, squishier side.

In 2008, Danna Staaf and her colleagues documented, for the first time, a humboldt squid egg mass, which they found in the Gulf of California. It is the only egg mass known to rival the one divers found in Turkey. The egg mass Dr. Staaf described was between 3 and 4 meters long, making it the largest ever recorded in the scientific literature. And the number of eggs inside? Oh, between 600 thousand and 2 million–ten times more than any other squid ever recorded (PDF of paper). That’s a lot of baby squid. But if egg masses like these are so huge, and produced by a common species like the humboldt or red flying squid, why aren’t they washing up everywhere?

One possibility has to do with depth. These egg masses are likely found much deeper in the ocean and only occasionally drift to shallow water. Another factor is time. Dr. Staaf and colleagues found that the developing squid in the giant mass took just three days to hatch (PDF of paper). That’s a pretty small window to find such a well-hidden target.

Unlike their parents, newly hatched squid from an egg mass like this are tiny and underdeveloped. Like baby birds, their eyes are not fully formed. Even worse, according to squid expert Dr. Liz Shea of the Delaware Museum of Natural History, their predatory tentacles are fused together in a little clump when they’re born. They may not even be capable of hunting on their own. How they grow into large raptorial predators is a complete mystery. It is possible that, like the giant egg mass itself, these larvae are destined for deeper depths–hiding out of sight until they develop the skills and ability to hunt, and perhaps lay car-sized egg masses of their own.

H/T to Christopher Mah of the echinoblog for sharing the video.

Edit 25 July 2015: An earlier version of this article misstated the nature of squid sucker teeth as being razor-sharp and barb-like. Though capable of scratching human skin, these teeth are not razor sharp and are not barbed.

Lovely write-up of this spectacular find! Given how sturdy their parents are, it’s amazing to note that ommastrephid egg masses are actually too fragile to wash up anywhere. If one did drift close to shore, the slightest surf or exposure to air would disintegrate it, scattering the eggs. And the eggs are so tiny, squishy, and translucent that even a million of them thrown on a beach would be nearly impossible to see!

A couple of small corrections about Humboldt squid: during numerous field seasons in Mexico, I never heard anyone, scientists or fishers or folks on the street, use the term “diablo rojo”–only “calamar gigante.” This has led me to suspect that “diablo rojo” may have been invented by sensationalist American media.

And the squid’s sucker ring teeth are neither razor-sharp nor barbed, though the scratches they leave can certainly be itchy and annoying.

Thank you for those clarifications.

Danna!!! Thanks for swinging by and for your lovely paper! Great to have an expert in the house! The egg masses are amazing to see! Have you found any before or since your paper was published? Also, thank you for pointing out details about the ring teeth. I’m surprised they’re not sharp! Are they hard? Can they break the skin? Thanks again for stopping by–love your blog!

Is it possible these are communal egg masses? The Humbold Squid do school. Perhaps they put all their eggs together? A group spawning behavior.

No, I haven’t found any more, sad to say! I did hear what seemed like a reliable account of recreational divers finding one off the Pacific coast of Baja (around 2010 I think?), but unfortunately no photos or video.

The sucker ring teeth are all chitin, no calcium, so they’re not as hard as the beak. They can sometimes break the skin, but they’re so small they can’t do much damage–their purpose for the squid is more like Velcro, to help the arms hold onto prey by slipping between fish scales or crustacean segments.

Thanks for the kind words. I’ve been a DSN fan for years and it’s an honor to see my paper show up here. =)

What about that luminous thing?

You mean inside the egg mass? I’m not entirely sure. I think it might just be an irregularity in the jelly, but I’m not positive.

I haven’t heard this idea, but I’m not sure anyone has seen these egg masses being produced. Interesting thought!

Such a good question! We wondered about that too; the main reason we think they’re produced by individual females is that the number of eggs in the mass (0.6-2 million) is roughly equivalent to the number of ripe eggs that other scientists have counted in a mature female’s oviducts (1.2 million). And the females actually have a lot more eggs waiting to mature in the ovary, so each female could lay up to 20 of these masses by the end of her life!!

WOW!

That’s amasing. So it’s mostly slime? Some kind of gel that expands in water?

Thanks for the info.

I filmed the French coast two years ago this sphere video I sent DORIS (website bio FFESSM) http://doris.ffessm.fr/forum_detail.asp?forum_numero=10827

And the assumption was the same as in your article.

The video is available on Vimeo:

https://vimeo.com/69025941

I dont know which part you guys are talking about. The part where the diver is shining their torch on a patch inside the blob at 1.22 or – at 2.53? It appears left centre and shoots up along the blob. Looks like bioluminescence? It has 6 dots, evenly spaced in a circle. What is this?

Yes, exactly! We don’t know exactly what the material consists of, but we’re pretty sure it’s produced by special glands inside the female’s body. It’s initially quite concentrated, then expands to form the large gelatinous matrix.

I am sure squid have to produce large numbers of eggs simply for survival. Six hundred thousand or two million are large numbers and tremendous numbers of little squid, but the survival rate is miniscule I am sure. I have never worked with them, but with their size as eggs and when hatched, they must be lunch for every creature that swims by.

That is an amazing image. We never stop learning!

This is very interesting!

Do you know near which part of Turkey this was sighted? which sea?

Why not Todarodes sagittatus (Lamarck, 1798), the european flying squid ? It probably reach much bigger sizes than Ommastrephes bartramii. Who says Ommastrephes bartramii can grow to around 1,5 meter in lenght ? There is obviouly a mistake !

Good question. You will have to ask Dr. Michael Vecchione. The total length (1.5 meters) is also from Dr. Vecchione, with a mantle length of 0.9 meters.