First, let’s be clear: in the ocean, mucus is king. On land, mucus is tragically confined to various animal orifices, unable to last long outside a moist environment. But in the ocean, slime is everywhere. And perhaps no animal has done more with ‘snot’ than the larvacean. Larvaceans are shaped like tadpoles, and most are pretty small, about as long as a rice grain. These tadpole-shaped animal have a big mucus complex: each larvacean lives inside its own little ball of goo (usually about as big as a marble), which it secrete from its skin like a disembodied nose with tail attached. The mucus “house” in which the larvacean resides captures particles much the way your nasal snot captures dust. And then the little larvacean slowly sucks in this snot, digests out the particles, and poops out little pellets. But just because an animal eats its own mucus for a living doesn’t mean it lacks sophistication. And nothing illustrates this point better than a 100 year old snotty mystery, solved by modern science.

The larvacean species known as Bathochordaeus charon was first described by a master jelly biologist, Carl Chun, in 1900. He named this ghostly creature after the first sight a Greek soul might see after death: Charon, the ferryman of Hades who shepherds souls across the river Styx and into the underworld. The name is fitting for such an evanescent creature. But in the 100 years since Chun’s work, this giant larvacean of the underworld was rarely seen, making some people wonder if it was even real.

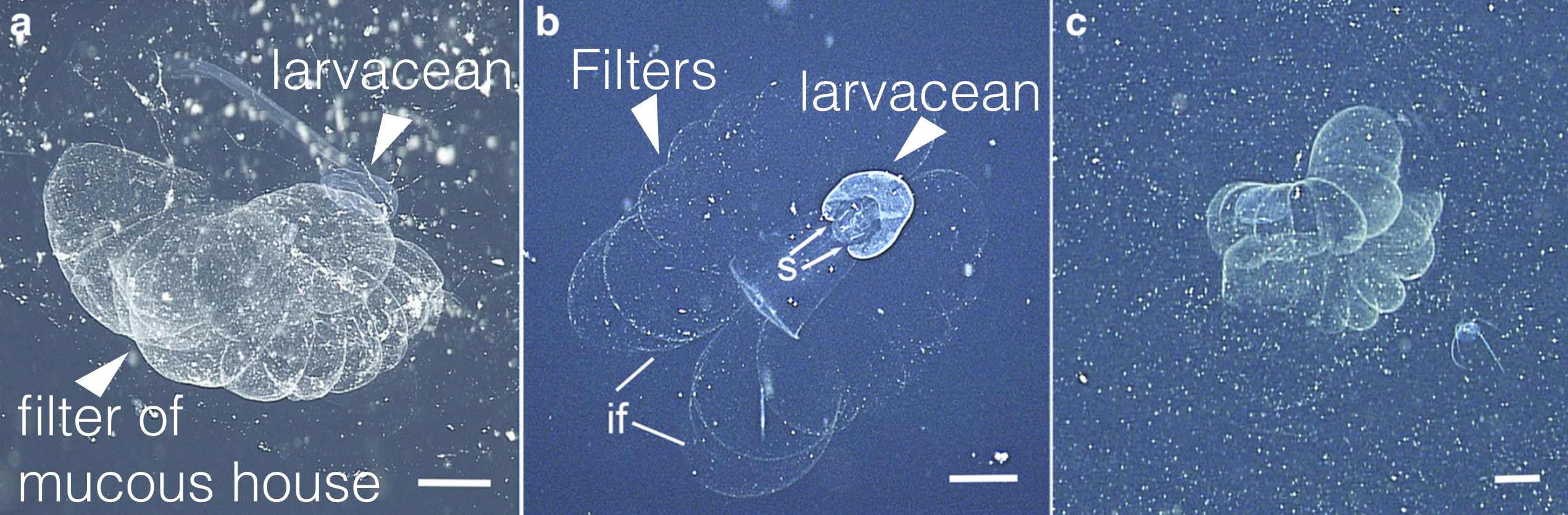

That is, until two scientists at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute found it, and published B. charon‘s 116 year-overdue debut in the journal Marine Biodiversity Records. And look at the beauty of this beastly snot fest:

Larvaceans like Bathochordaeus charon don’t just live in any old snot house; they live in mucus mansions, complete with delicate intakes, outflow canals, and finely-woven mesh through which water is filtered. An outer blobby layer of mucous serves as a kind of barrier, preventing larger objects from clogging the delicate internal filter (shaped like two ridged lobes). Tucked in the middle of this slimy palace, the larvacean creates a current by beating its tail, and the whole house slowly moves forward through the marine darkness, like its namesake ferryman over the river of the underworld.

And this ain’t no small house, either. While it’s true that most larvaceans are small, B. charon is a giant by normal standards. The larvacean itself clocks in over 7 cm (3 inches) in length. and the mucus house? Up to a meter wide!

While mucus might be king in the sea, in a watery world it also takes on an air of delicacy and beauty, and is far, far from icky:

This video is, I believe, of a close relative of Bathochordaeus charon: B. stygius (plus lots of other cool plankton after).