This is a guest post by Dr. Danna Staaf, a science writer with a PhD in marine biology from Stanford University. Her first book, Squid Empire: The Rise and Fall of the Cephalopods, chronicles the 500-million-year evolutionary journey of these fascinating animals. She also blogs at The Cephalopodiatrist.

Giant squid are the sea’s best monsters, tentacles down. For evidence we need look no further than the logo of this very website. But did you know that our beloved Architeuthis descends from a venerable line of sea monsters—that Archy’s ancestors, in fact, may have been the first animals ever to merit the name “monster”?

The phrase “prehistoric sea monster” might summon to mind an ichthyosaur or megalodon, but these are johnny-come-latelies to the underwater scene. Megalodon showed up a mere 23 million years ago. Ichthyosaurs evolved closer to 250 million years ago, which may seem pretty old (okay, it is) until you consider the age of the first cephalopod: 450 million years.

I’ll admit that initially cephalopods were no monsters. Snail-like, they lived inside shells that measured a few centimeters at most. But these shells contained a remarkable evolutionary innovation: sealed-off chambers that could be drained of fluid and filled with buoyant gas.

This buoyancy freed cephalopods from the constraints of their heavy shells, allowing them to reach stupendous sizes. No matter how big the shell grew, its weight was automatically offset by more gas-filled chambers.

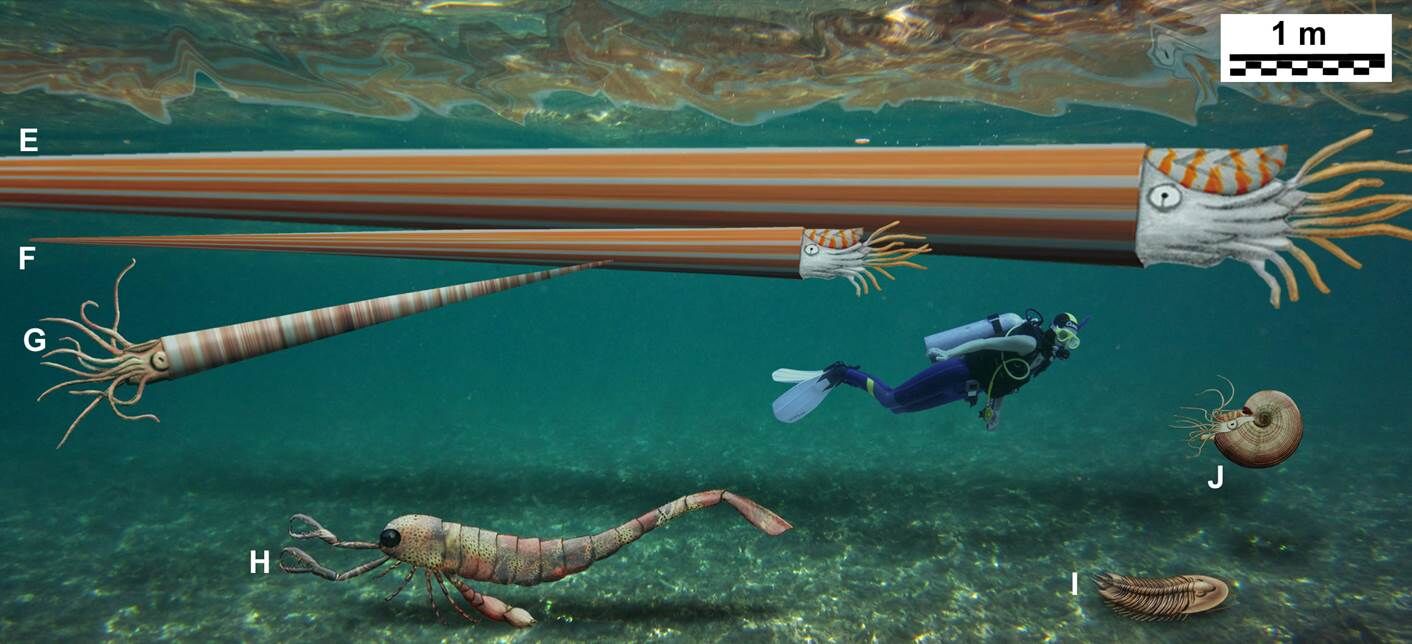

Endoceras giganteum, for example, grew up to 3.5 meters, longer than a basketball hoop is tall. It was the biggest animal the world had yet seen. I feel confident calling this 450-million-year-old beast one of the planet’s first monsters.

But how did we get from Endoceras to Architeuthis? Is one a direct ancestor of the other, or are they distant cousins n-times-removed? And what became of that fantastic shell?

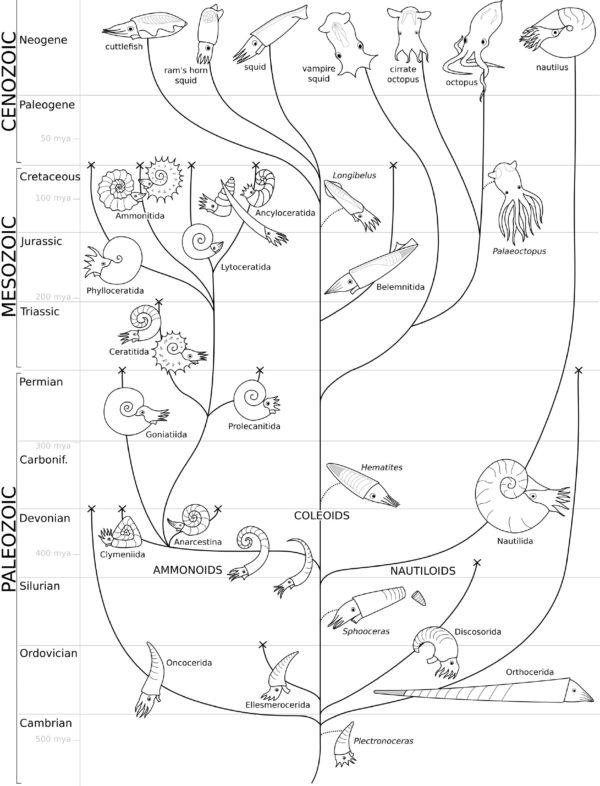

We need a family tree for Endoceras, Architeuthis, and everything in between—in other words, a cephalopod phylogeny. For over a century, scientists have been working to reconstruct such a phylogeny with evidence from fossils, embryos, DNA and more. I made an attempt to synthesize the most recent work into a single drawing, with lots of advice from paleontologists and the helping hand of an artist who polished my messy sketchwork (and put in those friendly eyes).

Endoceras was one of the Orthocerida, which you can find down in the Ordovician, in the lower right. Today’s giant squid take pride of place—with their smaller siblings—top and center. As for the rest…

From Cambrian through Silurian times, cephalopods all wore their shells on the outside of their bodies, just like every other self-respecting mollusk. The nautiloids continued that decorous habit to the present day. Another externally-shelled group, the ammonoids, explored every bizarre baroque extreme of shell coiling and ornamentation before getting mass-extincted alongside the dinosaurs.

What remains are the coleoids—the only group of cephalopods in which evolution sheathed the shell, burying hard structure inside a soft body.

At first, this internal shell was still massive and still full of buoyant chambers, as in the early coleoid Hematites. But over time natural selection (carried out by hungry fish, for the most part) favored smaller, simpler shells.

Now, cuttlefish and ram’s horn squid are the only modern coleoids to retain the hard calcium and buoyant chambers of their ancestors. The internal shells of octopuses have evolved into mere vestiges.

And squid? Well, the shell remnant of a squid has no chambers and no calcium. But it runs the full length of the body, from head to fin-tip, and it offers support to the powerful muscles that carry these modern monsters through the sea. Though unarmored, Architeuthis is most likely faster and far more agile than Endoceras could ever have dreamed of being.

So which one would you rather meet in a dark alley?

“Endoceras was one of the Orthocerida” No. Endoceras was one of the Endocerida: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Endocerida This is a completely different order of nautiloids.