The following is a guest post by Dr. Clark Richards, a physical oceanographer at the Bedford Institute of Oceanography in Halifax, Canada. It was originally posted on his personal blog. Clark is an expert in geophysical fluid dynamics, ocean robots and throwing really expensive stuff in the ocean in treacherous places.

Introduction

The Ocean Cleanup, brainchild of Dutch inventor Boyan Slat, was in the news again this past week after announcing that in addition to the fact that their system is unable to collect plastic as intended, it suffered a mechanical failure. “Wilson” is currently being towed to Hawaii, where it will undergo repairs and upgrades, presumably to be towed back out to the garbage patch for a second trial.

I am not a mechanical engineer, so I don’t intend to comment on the details of their mechanical failure. I am, however, a sea-going oceanographer. Which means that I am used to the sorts of situations with scientific research equipment that was so succinctly paraphrased by Dr. Miriam Goldstein:

![“The ocean is strong and powerful, and likes to rip things up.” ![Dr. Miriam Goldstein. Prescient oceanographer]](https://www.deepseanews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/MiriamTruths.jpg)

Designing for physics

But beyond the engineering, there are the questions of what the *physics* are that TOC are relying on for their system to be successful. Some of you may recall that the original design was to moor (i.e. *anchor*) their device in 6000m (20000 feet) of water, and let existing ocean currents sweep garbage into the U-shaped structure. Thankfully, they realized the challenges associated with deep-ocean moorings, and abandoned that idea.

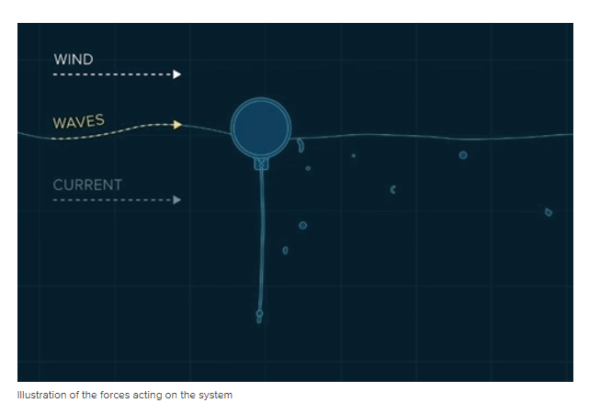

The latest design iteration (misleadingly called “System 001”, as though they haven’t built and tested any other previous to it), is to have a freely-drifting system, avoiding the use of anchors. TOC claim that under the influence of current, wind, and waves, their design will drift *faster* than the plastic — causing it to accumulate in the U, making for easy pickup. They summarize the concept with a little explainer video on their website, with a representative screen shot below:

Based on a quick Twitter rant that I had after thinking about all this for a few minutes (see here), I wanted to explain out the various points that have either a) been missed by TOC design team, or b) deliberately excluded from their rosy assessment of how they expect their system to actually collect garbage. What follows is a “first stab” at a physical oceanographic assessment of the basic idea behind “System001”, and what TOC would need to address to convince the community (i.e. scientists, conservationists, etc) that their system is actually worth the millions of dollars going into development and testing.

The premise

As outlined in the video, the premise of System001 as a garbage collection system is that through the combined action of wind, waves, and currents, the U-shaped boom will travel faster through the water than the floating plastic, thereby collecting and concentrating it for eventual removal. This appears to be based on the idea that while both the boom and the plastic will drift with the current, because the boom protrudes from the water (like a sail), it will actually move faster than the surface water by catching wind.

There are some issues with this premise. Or, at least, there are some real aspects of oceanography that have either been ignored or missed in thinking that such a system will behave in the predictable way described by TOC. I’ll try and outline them here.

Stokes drift

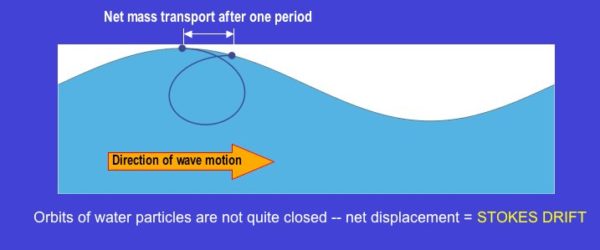

Any of you who may have had an introduction to ocean waves may have heard that during the passage of a wave, the water particles move in little circles (often called wave orbital motion). While not a bad “first-order” description, it turns out that for real ocean waves there is also some drift in the direction of wave propagation. This drift is named after Gabriel Stokes, who first described it mathematically in 1847 (see wikipedia article here).

The amount of drift depends nonlinearly on both the amplitude and the wavelength of the wave. For example, for a 0.5m amplitude wave with a wavelength of 10m and period of 10s (something like typical ocean swell), the drift velocity is about 10 cm/s right at the surface.

Of course, the Stokes’ solution describes the motion of the water parcels being moved by the wave. For those water parcels to then have an effect on anything in the water, one would need to consider the various components of force/impulse/momentum (i.e. our buddy Sir Isaac Newton). Needless to say, it seems obvious that a smallish piece of neutrally buoyant plastic will respond to the Stokes drift much more readily than a 600m long floating cylinder with a large mass (and therefore large inertia).

This alone could be enough to quash the idea of a passive propagating collection system. Mr Slat?

Ekman currents

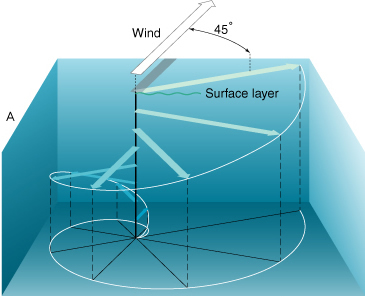

While we’re talking about long-dead European fluid mechanics pioneers, any study of the effect of winds and currents wouldn’t be complete without a foray into the theories proposed by Swedish oceanographer Vagn Walfrid Ekman in 1905. What Ekman found was that when the wind blew over the surface of the ocean, the resulting current (forced by friction between the air and the water) didn’t actually move in the same direction as the wind. The reason for this is because of the so-called “Coriolis effect”, whereby objects moving on the surface of the Earth experience an “acceleration” orthogonal to their direction of motion that appears to make them follow a curved path (for those who want to go down the rabbit hole, the Coriolis acceleration is essentially a “fix” for the fact that the surface of the Earth is non-inertial reference frame, and therefore doesn’t satisfy the conditions for Newton’s laws to apply without modification).

Anyway — the consequence is that in an ideal ocean, with a steady wind blowing over the surface, the surface currents actually move at an angle of 45 degrees to the wind direction! Whether it’s to the left or right of the wind depends on which hemisphere you are in — I’ll leave it as an exercise to determine which is which. And what’s cooler, is that the surface current then acts like a frictional layer to the water just below it, causing it to move at an angle, and so on, with the effect being that the wind-forced flow actually makes a SPIRAL that gets smaller with depth. This is known as the Ekman spiral.

The actual depth that the spiral penetrates to depends on a mysterious ocean parameter called Az, which describes the vertical mixing of momentum between the layers — kind of like the friction between them. What is clear though, is that a small particle of plastic floating close to the surface and a 3m deep floating structure will likely not experience the same wind-forced current, and therefore won’t move in the same direction. Hmmm … that’s going to make it hard to pick up pieces of plastic.

What is a “Gyre” anyway?

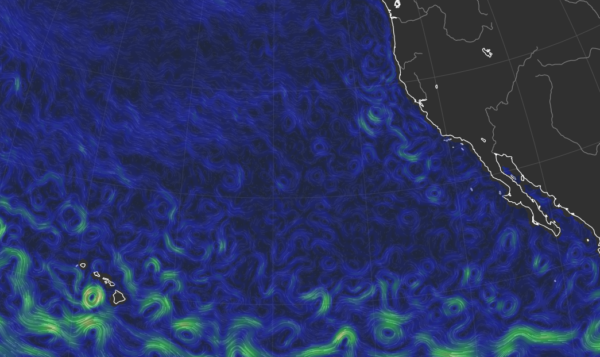

The final point I wanted to make in this article (I have more, which I’ll summarize at the end for a possible future article), is to try and give a sense of what currents in the ocean (including in the “gyre” or in the region often referred to as the “Great Pacific Garbage Patch”) actually look like. The conception that there is a great swirling current 1000’s of km across is true only when the currents are averaged for a very long time. At any given instant, however, the ocean current field is a mess of flows at various space and time scales. An appropriate term for describing typical ocean flow fields is “turbulent”, as in an oft-viewed video made by NASA from satellite ocean current data.

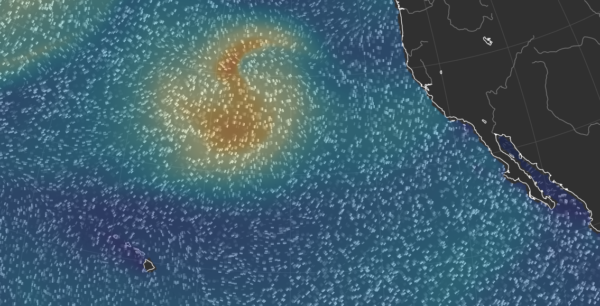

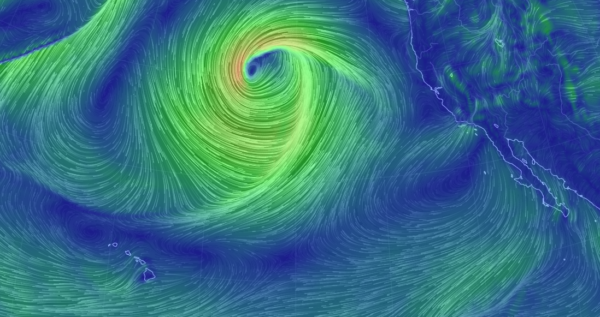

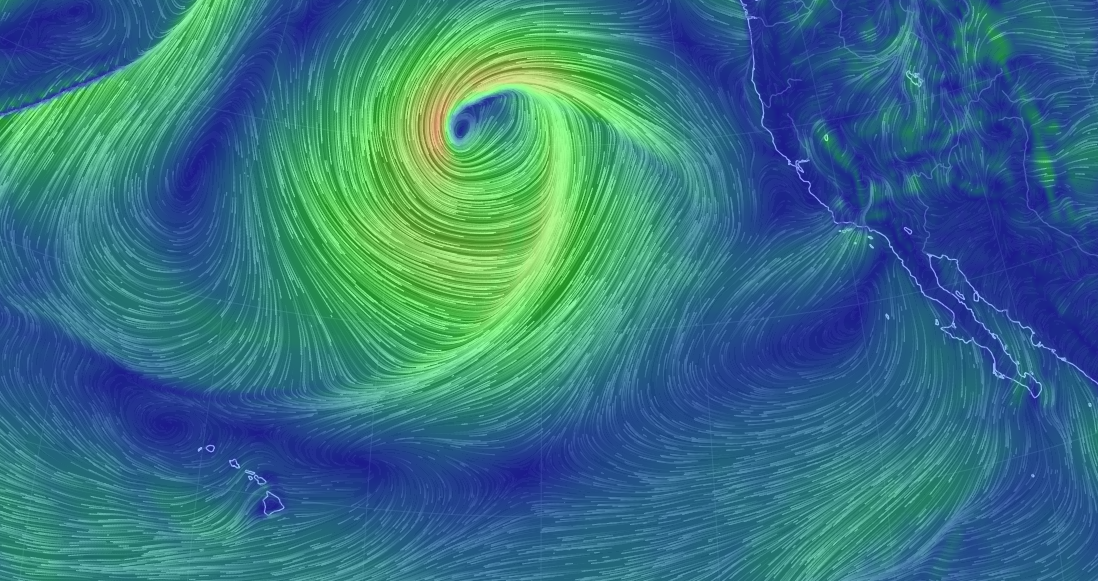

To illustrate this, I took some screenshots of current conditions from the wonderful atmosphere/ocean visualization tool at earth.nullschool.net showing: ocean currents, surface waves, and wind.

These images illustrate the potential problem with TOC idea, by highlighting the fact that the wind, wave, and current fields of the ocean (including even in the “quiet” garbage patch) are highly variable spatially and temporally, and are almost never aligned at the same period in time. What’s more, is that the currents and waves at a given time and location are not always a result of the wind at that location. Eddies in the ocean are generated through all kinds of different processes, and can propagate across ocean basins before finally dissipating.

Similarly, surface waves have been measured to cross oceans (i.e. the famous “Waves across the Pacific” study pioneered by the transformative oceanographer Walter Munk).

Other issues

Following the “rule of three”, I tried to hit what I consider to be the biggest concerns with TOC system design and principle, from my perspective as a physical oceanographer. However, there are other issues that should be addressed, if the system as designed is really believed by the TOC team to be capable of doing what they say. And really, it seems like a crazy waste of time on behalf of everyone involved to have spent this much time on something if they aren’t sure it will even work theoretically … not to mention the money spent thus far. So, part of me *has* to believe that all the dozens of people involved care deeply about making something that might actually work, and they have studied and considered all the effects and potential issues I (and others) have raised.

Anyway, the other issues are:

- What is the actual response of the system to a rapid change in wind/wave direction? Wind can change direction pretty quickly, especially compared to ocean currents. What’s to prevent a bunch of accumulated plastic getting blown out the open end of the U after a 180 degree shift in wind but before the system can re-orient?

- What about wave reflection from the boom structure itself? It is a well-known fact that objects (even floating ones) can reflect and “scatter” waves (scattering is when the reflected waves have a shorter wavelength than the original ones), and it seems like this could create a wave field in the U that might actually causes drift *out* of the system.

- The idea that all wildlife can just “swim under” the skirt (because it’s impermeable) is not supported by anything that I consider to be rigorous fluid mechanics, aside from the fact that much of what actually lives in the open ocean are non-motile or “planktonic” species. There are a lot of communities in the open ocean that float and drift at the surface, and I see no way that if the System collects floating plastic as it is designed that it won’t just sweep up all those species too. The latest EIA brushed off the effect of the System on planktonic organisms by stating that they “are ubiquitous in the world’s oceans and any deaths that occur as a result of the plastic extraction process will not have any population level effects”. But that doesn’t take into account that the stated mission is to deploy 60 such systems, which are estimated to clean the garbage patch of surface material at a rate of 50% reduction every 5 years. It stands to reason that they would also clean the Pacific of its planktonic communities by the same amount.

Hmmm…it’s almost like ocean wave mechanics is COMPLICATED or something! Methinks young Mr. Slat would’ve been well served finishing that engineering degree.

Thank you for your clear, concise breakdown.

I’ll admit that I haven’t been following the details of the development of the OC boom, but I have to ask: how do you undertake a project of this scale and only discover that it is fundamentally flawed after implementing a full-scale prototype? I mean, I take your point that you want a solid theoretical model, but how do you also not, y’know, throw some things in the ocean first? Didn’t they have a scale model in place in actual – or recorded on site and reproduced – conditions in the area they planned to deploy in? That seems like madness?

:What is clear though, is that a small particle of plastic floating close to the surface and a 3m deep floating structure will likely not experience the same wind-forced current, and therefore won’t move in the same direction. Hmmm … that’s going to make it hard to pick up pieces of plastic.”

Hold on, isn’t this disparity how they /would/ sweep up plastic?

But interesting explanation all around. It’s bizarre if they don’t have a credible simulation of the design before building the thing.

And the 45 degrees and Ekman spiral are fricking totally cool!

How does the 45 degrees operate near the equator? It can’t abruptly flip from + to – presumably. I sure don’t have a grasp of the physics, but my gut would say Coriolis effect would change smoothly with latitude, like a sine from pole to pole or something.

“For example, for a 0.5m amplitude wave with a wavelength of 10m and period of 10s (something like typical ocean swell), the drift velocity is about 10 cm/s right at the surface.”

Find the error…….;-)