An article by Bryan Wallace for Deep Sea News.

The deep-sea is as far removed from atmospheric oxygen as anyplace on Earth, but a select few air breathers are undeterred. (No, I’m not referring to intrepid deep-sea human researchers.) These extraordinary critters frequently venture into the deep-sea, despite their vital link to air the above the ocean’s surface.

The deep-sea is as far removed from atmospheric oxygen as anyplace on Earth, but a select few air breathers are undeterred. (No, I’m not referring to intrepid deep-sea human researchers.) These extraordinary critters frequently venture into the deep-sea, despite their vital link to air the above the ocean’s surface.

Colossal sperm whales plunge over 1,000 meters to battle giant squid in the dark abyss. Massive elephant seals chase prey more than an hour at depths > 1000 m. The deepest known divers are the beaked whales, with recorded dives to over 2,000 meters. What about turtles? Could a shelled reptile be suited for making dives where only a few whales and seals dare to go?

Leatherback turtles possess remarkable adaptations for long and deep dives. They have large onboard stores of oxygen in their blood and muscle, and special features like collapsible lungs (to avoid ‘the bends’), a pulmonary sphincter (to shunt blood flow away from the collapsed lungs and back to the body during dives), flexible shell (to respond to increased pressure at depth), and slowed heart rate (to conserve energy and oxygen stores). In fact, researchers have recorded leatherbacks diving to over 1,000 meters in different ocean basins (Doyle et al. 2008). Apparently, anything a whale can do, a turtle can, too.

Here’s a link to a National Geographic interactive showing leatherbacks’ anatomical and physiological adaptations for deep diving.

To be clear, leatherbacks spend most of their time within the top 300 m of the ocean. This is because they feed primarily on jellyfish, like lion’s mane jellies and sea nettles, which tend to be concentrated at or near the ocean’s surface (James et al. 2005). However, leatherbacks are clearly capable of – and undertake – much more ambitious diving. The obvious question is: what are leatherbacks doing down there?

At this point, we aren’t sure what motivates a leatherback to plunge thousands of meters away from their most critical resource, but there are a few possibilities. Like other deep-divers, they might be pursuing prey. (Let’s face it; food is a strong incentive for any animal.) Perhaps they shuttle between different water temperatures in order to keep their body temperature stable, so an occasional deep dive into frigid waters could offset the heating effects of strenuous diving. Or maybe, like many other marine animals, they use the deep-sea as refuge to evade hungry predators, such as sharks and orcas.

A recent study by researchers in the UK (Houghton et al. 2008) examined several hypotheses about why leatherbacks perform such extraordinarily deep and long-lasting dives using satellite transmitter-derived dive data. Their analyses led them to infer that these occasional sojourns to the deep are essentially to have a look around. Leatherbacks seem to use these deep dives as a way to scan the water column, potentially relying on chemical cues to orient themselves to potential food resources or oceanographic features.

What we know for certain is that leatherbacks are certainly unique among sea turtles in their special abilities reach profound depths and stay down for extended periods of time. These adaptations reveal evolution’s power and elegance because they converge so strongly with analogous adaptations in distantly related taxa like cetaceans, pinnipeds, and diving birds.

While leatherbacks have yet to reveal all of their secrets to us, hopefully our current efforts and those of our colleagues in other parts of the world will shed light on the dark side of leatherbacks’ deep-sea lives.

In the Great Turtle Race, we are using satellite telemetry to track male and female leatherback turtles migrating from feeding areas off Nova Scotia, Canada to breeding areas throughout the Wider Caribbean. Check out www.GreatTurtleRace.org to follow leatherbacks on their migration and to learn more about leatherbacks, the threats they face, and what is being done to protect them.

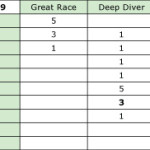

Given the leatherbacks’ superlative diving abilities, we are highlighting special swimming performances by leatherback turtles during the Great Turtle Race – the categories are 1) most deep dives, and 2) most long-lasting dives. These should be of particular interest to the DSN’s readers. The turtle who best proves its diving mettle will be crowned the ‘Iron Turtle’ by DSN at the end of these diving competitions.

Go to the GTR website to meet the turtle competitors, pick your favorite, and check in daily to GTR and DSN for updates on the Iron Turtle Competition!

Citations:

Doyle, T., Houghton, J., O Súilleabháin, P., Hobson, V., Marnell, F., Davenport, J., & Hays, G. (2008). Leatherback turtles satellite-tagged in European waters Endangered Species Research, 4, 23-31 DOI: 10.3354/esr00076

Houghton, J., Doyle, T., Davenport, J., Wilson, R., & Hays, G. (2008). The role of infrequent and extraordinary deep dives in leatherback turtles (Dermochelys coriacea) Journal of Experimental Biology, 211 (16), 2566-2575 DOI: 10.1242/jeb.020065

James, M., Myers, R., & Ottensmeyer, C. (2005). Behaviour of leatherback sea turtles, Dermochelys coriacea, during the migratory cycle Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 272 (1572), 1547-1555 DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3110

Are the phyisological adaptations in leatherbacks for prolonged dives the same/similar to those in cetaceans? The article seems to suggest so, but the citiations dont’ address it specifically… Marine Herp wasn’t an offering at UNC-W, so I honestly have no idea…

Yep, pretty much similar. Convergent adapations between leatherbacks and cetaceans/pinnipeds. They all show the ‘typical’ dive response, for example, but to varying degrees.

Leatherbacks’ blood and muscle oxygen stores are much lower than those of marine mammals, but then again so are their metabolic rates, so they can still do the prolonged dives.

Check out my other post about Gigantothermy and the paper cited there: Wallace and Jones (2008) JEMBE. We go over physiological adaptations for diving in leatherbacks there.

And if you’re at UNC-Wilmington, go look up Dr Amanda Southwood, if you haven’t already. She’s one of the premier sea turtle physiologists in the world -and a good buddy of mine!

good information, thanks

what is the lowest tempture that they can be in