From the darkness emerges a boot. An old leather, steel-toed, work boot. It shouldn’t be there resting on the seafloor nearly two kilometers deep. I’m speachless. Even knowin this was going to be one of the toughest dives of my career, I’m still not prepared.

Seven years prior in 2010, Marla Valentine and Mark Benfield were the first scientist to visit the deep-sea floor after the Deepwater Horizon accident. On 20 April 2010, and continuing for 87 days, approximately 4 million barrels spilled from the Macondo Wellhead making it the largest accidental marine oil spill in history. Just months after the oil spill, Valentine and Benfield conducted video observations with a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) of the deep-sea impact. Overall, they found a deep-sea floor ravaged by the spill. Much of the diversity was lost and the seafloor littered with the carcasses of pyrosomes, salps, sea cucumbers, sea pens, and glass sponges.

Researchers continued to find severe impacts on deep-sea life. The numerical declines were staggering within the first few months; forams (↓80–93%), copepods (↓64%), meiofauna (↓38%), macrofauna (↓54%) and megafauna (↓40%). One year later, the impacts on diversity were still evident and correlated with increases in total petroleum hydrocarbons (TPH), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH), and barium in deep-sea sediments. In 2014, PAH was still 15.5 and TPH 11.4 times higher in the impact zone versus the non-impact zone, and the impact zones still exhibited depressed diversity. Continued research on corals found the majority of colonies still had not recovered by 2017. However, studies examining the impacts of the DWH oil spill on most deep-sea life ended in 2014.

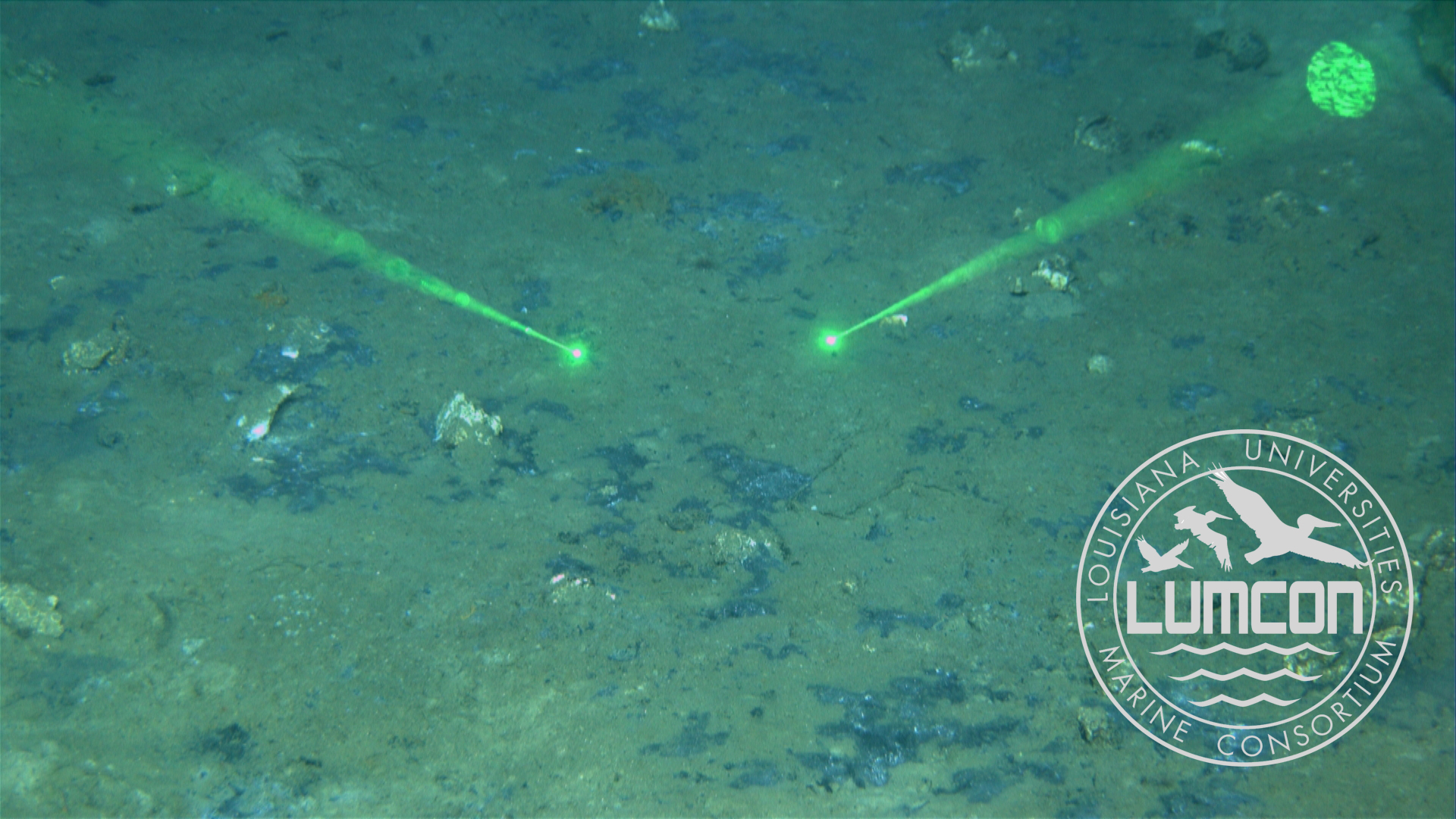

This gap in knowledge on the lingering impacts of one of the largest oil spills of all time is why I sit here in this cold, dark, ROV control room staring at a work boot in the abyss. A year prior, I had reached out to Mark Benfield about replicating his ROV methods and locations. I am here seven years after his study beginning to replicate his first video transect.

Within minutes of reaching the seafloor with the ROV, every scientist on the vessel staring at monitors showing live video from remote seafloor knew something was wrong. As Mark Benfield, Clif Nunnally, and I report in a new open-access article, the deep sea was not recovering at the impact site. The seafloor was unrecognizable from the healthy habitats in the deep Gulf of Mexico, marred by wreckage, physical upheaval and sediments covered in black, oily marine snow.

Near the wreckage and wellhead, many of the animals characteristic of other areas of the deep Gulf of Mexico, including sea cucumbers, Giant Isopods, glass sponges, and whip corals, were absent. What we observed was a homogenous wasteland, in great contrast to the rich heterogeneity of life seen in a healthy deep sea.

Conspicuously absent were the sessile animals that typically cling to any type of hard structure in an otherwise soft, muddy habitat. Hard substrate in the deep sea is a valuable commodity but at the Deepwater Horizon site metal and other hard substrates were devoid of typically deep-sea colonizers.

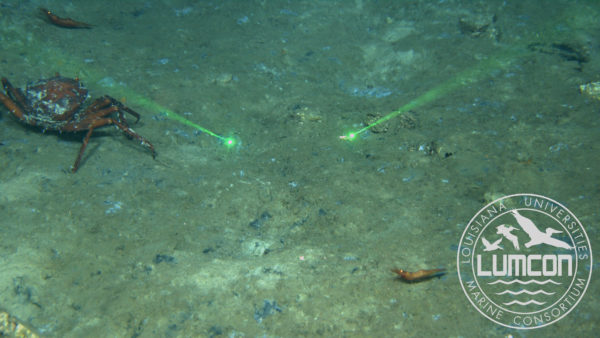

The seafloor at impact site was characterized by high numbers of shrimps and crabs. Crabs showed clearly visible physical abnormalities and sluggish behavior compared to the healthy crabs we had observed elsewhere. We believe these crustaceans are drawn to the site because degrading hydrocarbons serve as luring sexual hormone mimics. Once these crustaceans reach the site they may become too unhealthy to leave much like those prehistoric mammals and the Le Brea tarpits.

The ROV dive began with a boot belonging to one of the workers on the Deepwater Horizon rig. The dive ended at the wellhead, now capped with a memorial to those workers who lost their lives. A dive bookended with reminders of the human tragedy of the oil spill. The narrative that unfolded between these was an environmental catastrophe. In an ecosystem that measures longevity in centuries and millennia the impact of 4 million barrels of oil continues to constitutes a crisis of epic proportions.

Valentine, Marla M., and Mark C. Benfield. “Characterization of epibenthic and demersal megafauna at Mississippi Canyon 252 shortly after the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill.” Marine Pollution Bulletin 77.1-2 (2013): 196-209.

McClain, Craig R., Clifton Nunnally, and Mark C. Benfield. “Persistent and substantial impacts of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill on deep-sea megafauna.” Royal Society Open Science 6.8 (2019): 191164.

Share the post "The lingering and extreme impacts of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill on the deep sea"