The worn and weary phrase “There’s more fish in the sea” isn’t just cold solace for heartbroken saps, but for shark biologists, this means more discoveries of new species.

Another year of science closes, giving us pause to review those new species of sharks described in the scientific literature, bringing the total number of known shark species to 512. Perhaps it’s a hollow victory to have so many different species known at a time when sharks populations worldwide are either in decline or in a complete population tailspin. But as taxonomists continue to kick ass and give names, our knowledge of shark evolution, biogeography, and ecology continue to get richer. Meet the new sharks of 2015:

Ginglymostoma unami, the Pacific Nurse Shark

This isn’t really the brand-spankin’ new species you might think, but it has been known for well over a century. The Nurse Shark (Ginglymostoma cirratum) had a disjunct distribution between the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico and the eastern central Pacific oceans, meaning their range was divided into two separate populations. Like some nooks in the Ozarks, land barriers prevented gene flow, so the populations were both physically and genetically separated by a small spit of land called Central America. This team didn’t use genetic methods to test if the populations were distinct enough to be considered different species, but relied on a meristics, the process of compiling detailed measurements of the shark’s anatomy and comparing these values between the populations. However, a 2012 paper on populations genetics of G. cirratum showed that the Pacific population was genetically quite unique, and divergent from any of the Atlantic populations. Since these two nurse shark populations had been separated by three million years, a few things can happen, like speciation. Indeed, their analysis showed that these two species are morphologically different enough to warrant giving the Pacific population its own scientific name. This name, G. unami, is an acronym of their alma mater, the Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico.

This isn’t really the brand-spankin’ new species you might think, but it has been known for well over a century. The Nurse Shark (Ginglymostoma cirratum) had a disjunct distribution between the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico and the eastern central Pacific oceans, meaning their range was divided into two separate populations. Like some nooks in the Ozarks, land barriers prevented gene flow, so the populations were both physically and genetically separated by a small spit of land called Central America. This team didn’t use genetic methods to test if the populations were distinct enough to be considered different species, but relied on a meristics, the process of compiling detailed measurements of the shark’s anatomy and comparing these values between the populations. However, a 2012 paper on populations genetics of G. cirratum showed that the Pacific population was genetically quite unique, and divergent from any of the Atlantic populations. Since these two nurse shark populations had been separated by three million years, a few things can happen, like speciation. Indeed, their analysis showed that these two species are morphologically different enough to warrant giving the Pacific population its own scientific name. This name, G. unami, is an acronym of their alma mater, the Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico.

Scyliorhinus ugoi, Dark Speckled Catshark

Way down among Brazilians sharks once swam there in the millions, but overfishing took surely took a hefty toll, yet there are still new shark species to be found. Case in point: a new catshark that had long been swimming along most of the Brazilian coast but had been confused as other known species. Catsharks are a widespread, diverse, and somewhat confusing group of sharks. Differences in color, morphological changes between juveniles & adults, and sexual differences between males & females create difficulties in sorting out just how many species there are. Here, the authors use detailed meristic analysis to extract out a species that had been there all along, but the morphological features that delineate the species had not yet been defined.

Way down among Brazilians sharks once swam there in the millions, but overfishing took surely took a hefty toll, yet there are still new shark species to be found. Case in point: a new catshark that had long been swimming along most of the Brazilian coast but had been confused as other known species. Catsharks are a widespread, diverse, and somewhat confusing group of sharks. Differences in color, morphological changes between juveniles & adults, and sexual differences between males & females create difficulties in sorting out just how many species there are. Here, the authors use detailed meristic analysis to extract out a species that had been there all along, but the morphological features that delineate the species had not yet been defined.

Atelomycterus erdmanni, Spotted-belly Catshark

This sexy beast is one of the more colorful species of catsharks, and is one of several new species discovered from a larger taxonomic mess called the coral catsharks. Using meristics, genetics, and biogeographical analyses, it turns out that the “coral catshark” represents several species, with this species as the newest. They don’t live in coral, so much as they crawl on and among coral reefs of Indonesia, using their pectoral and pelvic fins like tiny feet and walking like a more limber and agile salamander. Named after Mark Erdmann, a fish taxonomist who collected most of the known specimens, and was rewarded with this li’l shark bearing his name.

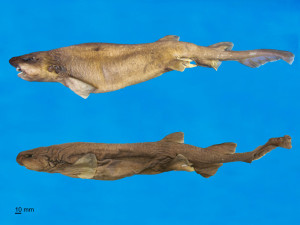

Bythaelurus tenuicephalus, Narrow-head Catshark

2015 also brought us two more catsharks, from the same genus, and both from the depths of the southwestern Indian Ocean. Hailing from the outer continental shelf of Mozambique and Tanzania comes the Narrow-headed catshark. The vast majority of sharks in recent years have been from the more remote pockets of Earth’s oceans, and in particular, from the deep oceans that have barely been explored. This species of Bythaelurus is a “dwarf”, a species that is sexually mature at a much smaller size than most other species in its genus. The advantage of dwarfism might allow this species to breed at a younger age, thus increasing their overall lifetime reproductive output. Or it could be that being smaller simply means eating smaller prey that larger species of catsharks might miss. This sort of niche-partitioning may explain why there are so many different species of catsharks. The species name tenuicephalus means “narrow head”, a little less imaginative than some names, but descriptive nonetheless.

2015 also brought us two more catsharks, from the same genus, and both from the depths of the southwestern Indian Ocean. Hailing from the outer continental shelf of Mozambique and Tanzania comes the Narrow-headed catshark. The vast majority of sharks in recent years have been from the more remote pockets of Earth’s oceans, and in particular, from the deep oceans that have barely been explored. This species of Bythaelurus is a “dwarf”, a species that is sexually mature at a much smaller size than most other species in its genus. The advantage of dwarfism might allow this species to breed at a younger age, thus increasing their overall lifetime reproductive output. Or it could be that being smaller simply means eating smaller prey that larger species of catsharks might miss. This sort of niche-partitioning may explain why there are so many different species of catsharks. The species name tenuicephalus means “narrow head”, a little less imaginative than some names, but descriptive nonetheless.

Bythaelurus naylori, Dusky Snout Catshark

Another year, another catshark on the list. This species however, has quite an interesting story behind its capture. Massive trawlers, towing huge nets and pulling up tons of fish aren’t new, but what is new is the trend for these huge vessels to move from depleted fishing grounds in the shallows, and into the relatively untapped fishery resources of the deep sea. In addition to the targeted commercial species that will earn them great sums of money when they return to port, these nets also catch and kill tons of other non-marketable species. This is what ecologists call ‘by-catch’, but there is a sunny side to such needless destruction. Commercial vessels are often the first to explore deep-sea zones, well ahead of research cruises that are difficult to fund and even more impossible to sustain over time. If you can get onto one of these factory trawlers, the bounty of the bycatch is yours, and what a paradise this is to shark researchers. Dave Ebert & Paul Clerkin of the Pacific Shark Research Center at Moss Landing Marine Lab got the invite to board one of these vessels as it sailed south from Mauritius, but with a small catch: they had to stay for the entire three month trawling season. If you haven’t ever had the displeasure of sailing the wild waves and howling winds where the Indian Ocean meets the Southern Ocean, then you wouldn’t know that it makes The Deadliest Catch look like a Honolulu harbor cruise. Already hardened by the seas of the Gulf of Alaska, Paul made three of these cruises, collecting more than a dozen new species of skates, rays, sharks, and chimeras that will be published in future years. The species name naylori honors Gavin Naylor of the College of Charleston who, through genetic analysis, is compiling a more complete evolutionary history of extant shark species.

Another year, another catshark on the list. This species however, has quite an interesting story behind its capture. Massive trawlers, towing huge nets and pulling up tons of fish aren’t new, but what is new is the trend for these huge vessels to move from depleted fishing grounds in the shallows, and into the relatively untapped fishery resources of the deep sea. In addition to the targeted commercial species that will earn them great sums of money when they return to port, these nets also catch and kill tons of other non-marketable species. This is what ecologists call ‘by-catch’, but there is a sunny side to such needless destruction. Commercial vessels are often the first to explore deep-sea zones, well ahead of research cruises that are difficult to fund and even more impossible to sustain over time. If you can get onto one of these factory trawlers, the bounty of the bycatch is yours, and what a paradise this is to shark researchers. Dave Ebert & Paul Clerkin of the Pacific Shark Research Center at Moss Landing Marine Lab got the invite to board one of these vessels as it sailed south from Mauritius, but with a small catch: they had to stay for the entire three month trawling season. If you haven’t ever had the displeasure of sailing the wild waves and howling winds where the Indian Ocean meets the Southern Ocean, then you wouldn’t know that it makes The Deadliest Catch look like a Honolulu harbor cruise. Already hardened by the seas of the Gulf of Alaska, Paul made three of these cruises, collecting more than a dozen new species of skates, rays, sharks, and chimeras that will be published in future years. The species name naylori honors Gavin Naylor of the College of Charleston who, through genetic analysis, is compiling a more complete evolutionary history of extant shark species.

And lastly….

Etmopterus benchleyi, Ninja Lanternshark

If you haven’t already seen this sassy new deepsea shark that went viral late last year, check it out here, and here, and here. That makes six new sharks for 2015, but new species will be discovered and described in 2016, so check back next year.

If you haven’t already seen this sassy new deepsea shark that went viral late last year, check it out here, and here, and here. That makes six new sharks for 2015, but new species will be discovered and described in 2016, so check back next year.

Etmopterus benchleyi n. sp., a new lanternshark (Squaliformes: Etmopteridae) from the central eastern Pacific Ocean: Journal of the Ocean Science Foundation; 17: 43-55.